All About GRAS: A Regulatory Framework for Ensuring Food Safety

At Perfect Day, we’re introducing an entirely new animal-free category of foods. We’ve started with animal-free milk proteins, ingredients that deliver the creamy goodness consumers love and expect from dairy products.

For the first time in history, we’ve found a way to uncouple dairy production from cows. Our mission is to change the process for making delicious products — without changing the foods themselves. We do this through precision fermentation.

Naturally, people have questions about the safety of making milk protein in new ways — namely, through fermentation, as Perfect Day does. It’s always important to ask whether your food is produced safely, and more so when the food (or the process used to make it) is new to the world. As a pioneer in the animal-free protein space, we have a responsibility to answer this critical question.

A multifaceted regulatory landscape works to ensure the safety of food ingredients. This article addresses one of those facets: the Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) Notification Program. The GRAS Notification Program is a transparent and public process overseen by the United States Food and Drug Administration and staffed by expert scientists.

Two Paths to Market: Food Additives vs. GRAS Ingredients

In 1958, Congress passed the Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). This amendment formally defined what food additives are — and, importantly, what they’re not.

Broadly, a food additive is any substance added to food during its production, processing, treatment, packaging, transportation, or storage.1 The 1958 amendment established a federal rule requiring that all food additives be subject to premarket approval — that is, the FDA must evaluate and approve these ingredients via formal notice and comment rulemaking (a process for notifying the public and soliciting comments about proposed regulations) before they can be used in food products.

However, the 1958 amendment includes another classification that is exempt from the food additives definition and regulation. Ingredients that are generally recognized by experts as safe based on their long history of use in food prior to 1958, or based upon published and widely available scientific evidence, are determined to be GRAS, and are not subject to premarket approval.2 (GRAS notice is the pathway that Perfect Day pursued for our non-animal whey protein; more on the basis for our GRAS determination below.)

“Intended Use” is a key part of both GRAS notices and food additives undergoing premarket approval. In either pathway to market, determination of safety is always based on how the ingredient will be used in food — specifically the function (for example, to bolster nutritional content or lend some other attribute) and the amount that will be used in food products.

Public vs. Private Data

The safety standards for both GRAS notices and food additive petitions are the same. The difference between the two pathways to market is in whether the data supporting safety determinations is publicly available.

For an ingredient to be deemed GRAS there must be a demonstrable consensus among qualified experts (“general recognition”) that the ingredient is safe for its intended use. This general recognition of safety comes from the total weight of published, peer-reviewed scientific literature and history of the ingredient’s common use. GRAS notification is a voluntary and transparent public process, meaning that the company filing the notice must gather all published and available safety data — including favorable and unfavorable studies — and submit it to the FDA. This submission is essentially a statement from the company saying, “We’ve determined that this ingredient is safe, and here’s the body of literature and scientific evidence that led us to our determination.”

Upon receipt, the FDA reviews all the information submitted in the GRAS notice, as well as any other publicly available information. They can request additional information as needed, including details about the production process. If they also find that the weight of evidence supports the ingredient’s safety, they respond with a public acknowledgment stating that they do not question the basis of the GRAS determination (more on this below). The entire process, and all relevant information supporting a determination of safety, are made publicly available on the FDA’s GRAS Notice Inventory.

The GRAS Notice Inventory is a database of all GRAS notifications that have been voluntarily submitted to the FDA for review. The GRAS Inventory provides both food makers and everyday consumers with information about how new food ingredients will be used, and the justification by which those ingredients are deemed safe.

Although the safety standards for food additives are just as rigorous as for GRAS ingredients, their pathway toward market approval works differently. For approval of a food additive, non-public safety information is submitted to the FDA for evaluation under a Food Additive Petition, for which general recognition among qualified experts is not required.

Safety data may be non-public, for example, if the substance is completely novel or is intended for new uses for which a robust body of published, peer reviewed studies are not yet available in the public domain. Such would be a clear case for a Food Additive Petition; GRAS would not be an option because general recognition of safety cannot be determined without published, peer-reviewed, and publicly-accessible data to demonstrate general recognition of safety by qualified experts, or a documented history of use in food.

Instead, with a Food Additive Petition, the company submits their own proprietary data on safety testing, feeding studies, and toxicological information for the additive. The FDA — not the company submitting the data — makes the expert determination of safety. The FDA then publishes a proposed regulation to authorize the food additive for specific intended uses in the Federal Register, inviting the public and other interested parties to submit comments to the agency for consideration ahead of a final regulation. This is a key difference from the GRAS process, wherein the company makes the GRAS determination based on public information, and then reports it to the FDA.

Benefits of the GRAS Notification Program

The FDA’s GRAS Notice Program is one of the most transparent and robust food regulatory programs in the world. It allows food makers to leverage existing scientific consensus based on publicly available data to bring safe, nutritious, and functional ingredients to market. Importantly, it does this without having to generate entirely new, proprietary data, eliminating the additional resources, lengthy timelines, and formal notice-and-comment rulemaking process required for a Food Additive Petition.

The GRAS program has a remarkable world-leading safety record, but also accounts for new developments in science by allowing for ongoing review of ingredients. Notably, an ingredient’s GRAS status can be revoked by the FDA if new scientific evidence arises that leads experts to question its safety, as in the case of partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs) in 2015.3 PHO’s have been present in foods (and occur naturally in some foods) for many decades. However, over time, as the body of scientific evidence around the potential health effects of PHOs evolved, it caused expert consensus to shift. FDA re-evaluated the scientific evidence and revoked the GRAS status of PHOs. Put another way, they developed new questions about the original GRAS, which was based on the history of use in foods, and revoked the status once there was no longer general recognition of safety for PHOs, acknowledging publicly that the science no longer reflected a clear consensus of PHOs’ safety.

The GRAS program is so robust, efficient, and well-regarded across the globe that many international companies will pursue GRAS determination through the FDA even before pursuing regulatory approval in their home countries. By maintaining a list of ingredients affirmed by experts as safe, the FDA offers a shorter path to market for new products, empowering food makers to respond quickly to consumer demands.

How is GRAS Determined by the FDA?

The process of submitting a GRAS notification often begins with an optional meeting with the FDA to discuss any questions or issues the notifier should be aware of when submitting their notice.

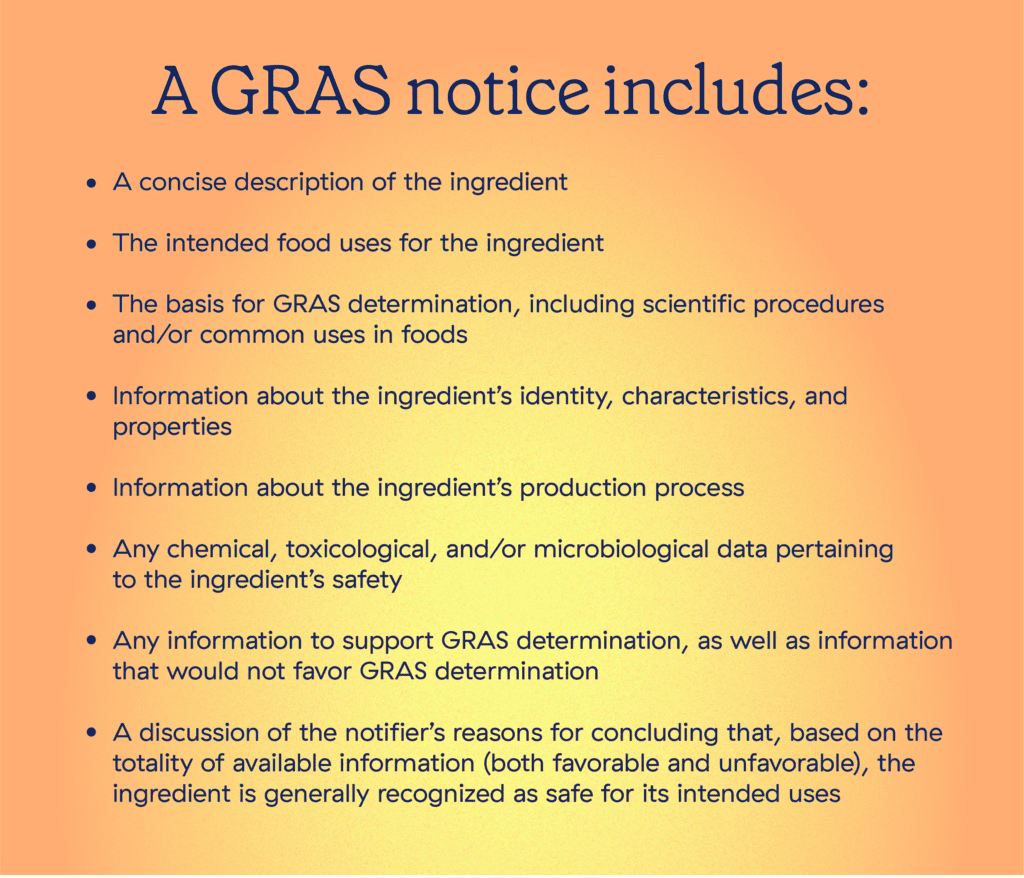

To initiate the process, the notifier compiles what’s called a GRAS exemption claim, known informally as a GRAS notice. “Exemption” here refers to being exempt from premarket approval per the FD&C Act. In other words, the notifier is claiming that the ingredient is not a food additive but rather an ingredient that is generally recognized by experts as safe, and is therefore not subject to premarket approval.

Upon receipt of a GRAS notice, the FDA reviews the documentation and evaluates whether the information forms a sufficient basis for the ingredient’s GRAS determination. GRAS evaluations are just as rigorous as those for food additive petitions, and they cover not only privately-held documentation, but the entire body of relevant published safety and toxicology studies in the public domain. Submissions are also posted to the GRAS Notice Inventory, where anyone at any time can find out where in the evaluation process a substance is.

Following the evaluation, the agency responds in one of three ways. The first is what’s referred to as a “no questions” letter. In issuing a “no questions” letter, the FDA acknowledges that they agree with the basis of the notifier’s determination of safety and have no further questions.

The second type of response is a letter in which the FDA contends that the evidence does not form a sufficient basis for GRAS determination. This may be based on missing data pertinent to safety, or because the available data raise doubt about the ingredient’s safety. Notifiers who receive this second type of response must provide additional information to the FDA before GRAS status can be affirmed.

The third type of letter is a public acknowledgment that the FDA has, at the notifier’s request, ceased evaluation. The FDA would issue this kind of response only if the notifier voluntarily withdraws their GRAS notice.

GRAS Determination for Animal-Free Whey

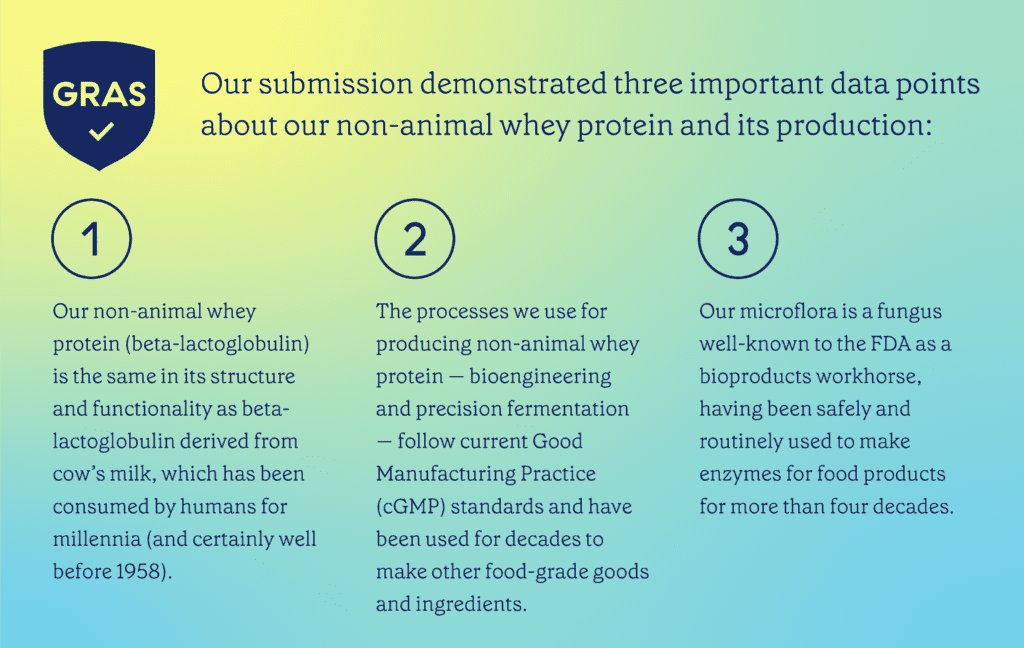

When Perfect Day was founded in 2014, we already knew that GRAS determination would be an important step toward bringing animal-free foods to market. Early on, we proactively reached out to the FDA, which confirmed that GRAS notification was the right path forward and advised us on the steps we should take to ensure consumer safety. We submitted a GRAS notice for our non-animal whey protein in March 2019 and received a “no questions” letter from the FDA in March 2020.

In the notice, we outlined the ingredient’s intended use as a non-animal protein replacement in food products that would otherwise use bovine milk protein or plant-derived protein.

Because we work with a well-known organism and use established precision fermentation processes to make the same milk protein that cows’ bodies make — and which humans have consumed for millennia — the FDA had no questions regarding the GRAS determination of animal-free whey protein for use in food products.

Click here to view Perfect Day’s GRAS notice and the FDA’s “no questions” letter in the GRAS Notice Inventory.

GRAS Notification vs. Self-Affirmed GRAS

Under the FD&C Act, GRAS notification to the FDA is voluntary. Companies can declare self-affirmed GRAS without notifying the FDA or sharing their safety data publicly.4 It is important to note, however, that if a company declares self-affirmed GRAS status, but is found to not meet all the GRAS requirements outlined above, that company would be operating in violation of the law and subject to enforcement by the FDA.

For us, stopping at merely self-affirmed GRAS status was not an option. We knew that the FDA’s public evaluation of our safety data would be a critical step in ensuring a timely path to working with partners, engendering consumer trust, and ultimately to bringing animal-free foods successfully to market.

Looking Ahead

We’re on a mission to transform the food industry with dairy ingredients that circumvent the downsides of animal agriculture. But we couldn’t achieve our mission without ensuring our product’s safety. This is why we took the early step of securing GRAS determination with the FDA, the world’s leader and our nation’s guardian of food safety. With this validation in hand, we are excited to move forward with partners to supply new animal-free foods — now more delicious and nutritious than ever — to all aisles of the supermarket.

As originators of a brand new, animal-free category, we recognize the tremendous responsibility we owe consumers to ensure safety and transparency. To this end, we are strong proponents of regulations that maximize transparency and safety, and we’ve worked closely with the FDA since our founding. We believe that the robust oversight the FDA’s GRAS Notification program provides is a benefit to consumers and food companies alike. We’ll continue to support and work with FDA to bring wholesome products to consumers that make the world better.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and International Food Information Council (IFIC). (2010, April). Overview of food ingredients, additives & colors. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/overview-food-ingredients-additives-colors

- Gaynor, Paulette. (December 2005/January 2006). How U.S. FDA’s GRAS Notification Program works. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/how-us-fdas-gras-notification-program-works

- Watson, Elaine. (2015, June 15). FDA revokes GRAS status of partially hydrogenated oils; allows food industry to file petition to permit specific uses. Food Navigator – USA. https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2015/06/16/FDA-revokes-GRAS-status-of-partially-hydrogenated-oils

- Bigelow, Sanford. (2012, April 10). The ability to self-affirm the safety of novel food and dietary supplement ingredients and market them on your own recognizance. Experts.com. https://www.experts.com/articles/safety-of-novel-food-and-dietary-supplement-ingredients-by-sanford-bigelow

We’d love to hear your thoughts!

Your email address will not be shared.